Coining the phrase ‘bazaar painters’ in a 1985 article, Metin And enriched our art history terminology with a new concept as well as offer a glimpse into the world of these artists: how they worked, what they drew, where their works are today and how they contribute to our study of history of art and culture. He continued to promote and popularise their work through books and articles published until 2007, at times repeating earlier content as required.

Bazaar painters and their work were not initially identified as a distinctive genre; Franz Taeschner, the first researcher to publish a selection, felt no need to refer to them as anything other than ‘miniatures’. Challenging this trend, Metin And set about the immensely difficult task of obtaining pictures of bazaar painting albums from four corners of the globe in order to illustrate a prolific series of essays and books.

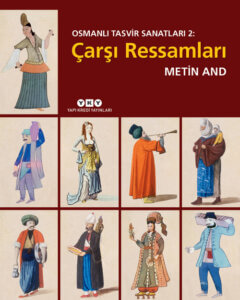

The second volume of Ottoman Figurative Arts, Bazaar Painters consists of twelve articles published between 1985 and 2007, a comprehensive introduction by Tülün Değirmenci, and a concise album. The pictures and inscriptions Metin And chased enthusiastically all his life are but the echoing footsteps of a book, one that was either never written, or somehow got lost before it could be published…

Contents

Preface / M. Sabri Koz

Ottoman Bazaar Painters • 7

Introduction / Tülün Değirmenci

Evolution of the Bazaar Painting and Metin And • 11

BAZAAR PAINTERS

Seventeenth-Century Turkish Bazaar Painters • 43

The Place and Importance of Bazaar Painters in Turkish Art • 53

Royal Portraits by Seventeenth-Century Turkish Bazaar Painters • 67

Seventeenth-Century Bazaar Painters and the Documentary Value of Their Work • 77

Bazaar Painters • 89

Musician Concubines as Seen by Turkish Bazaar Painters • 103

Ottoman Costume Book Presented to the Prussian Ambassador by Abdülhamid I • 115

Bazaar Painters • 125

A Bazaar Painter Album in Warsaw • 129

Istanbul’s Hawkers as Seen by Bazaar Painters • 139

A Two-Volume Istanbul Album by an Unidentified Bazaar Painter • 147

The Harem as Seen by Bazaar Painters • 159

ALBUM • 167

Abbreviations • 231

Bibliography • 233

Index • 237

Preface: Ottoman

Bazaar Painters

M. Sabri Koz

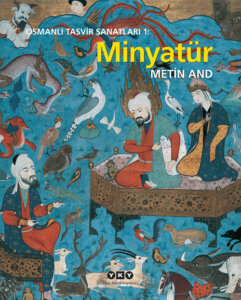

Metin And was a Renaissance man, one who would have been described as a ‘hezârfen’ in a bygone era. I beg the reader’s indulgence in a partiality for this oldfashioned, yet timeless adjective meaning ‘possessor of a myriad sciences’. The combination hezârfen Metin And sounds anything but strange, quite the opposite: it is an invitation to an engrossing journey. This adjective hardly does justice to someone –a big child– who leapt from reading Law to the arts, and every branch of the arts, paving innovative, valuable and lasting ‘new’ paths in everything he put his mind to. I had been a fan since college when I read his articles (all in Turkish) in Turkish Folklore Studies and his Dionysus and the Anatolian Villager (1962) and Traditional Turkish Theatre: Puppets, Shadow Play, Theatrein-the-Round (1969); that I was fortunate enough to serve and assist my hero, to be part of the final seven years of his life through his connection with YKY was my consolation prize. It has been exactly ten years since he passed away. Death of the industrious grieves doubly; we mourn the deceased, and lament the unfinished work. So it was with him. Those who are left behind cannot always finish it; even if they could, it would –could– never be quite as the originator had envisaged it. I knew him well enough to state here that Metin And left behind very few unfinished files. What he wasn’t able to write or publish was not due to want of trying. He did want to publish an expanded Turkish version of André Antoine’s Chez les Turcs with additional documents and pictures; And had in 1965 published the book by the founder of the City Theatres. Who knows, that material might yet be found, or a Turkish translation might be eventually published with an introduction by an expert on the history of City Theatres. Pursuing Wizards is an entertaining and informative file, missing only one final chapter. It has been typeset and proofread; all it needs is his daughter Esra And’s input on the illustrations, and the grace of an editor proficient in the art. There is no need to mention Metin And’s other books awaiting reprints; like the rest, they are all awaiting the end of these prolonged labour pains. Many book proposals consisting of And’s articles are on the editor’s agenda; what time and circumstances will allow, however, is unknown. In my preface to the YKY edition of Ottoman Figurative Arts I: Miniature, I had mentioned the content of a second volume that Metin And had been planning to write; I had also expressed my wish to prepare a compilation in the future, even though it would never be quite what he had in mind. I had also added that Metin And’s framework could only cover the art of bazaar painters; the other topics would have to be left out. Some of us who had come to pay our respects had gathered around two members of his family in the courtyard of Teşvikiye Mosque: his brother Tuncay Çavdar and his daughter Esra And. Tuncay Çavdar said, ‘My brother had wanted to prepare Bazaar Painters; I’m not sure what happened. It would be great if you could publish it,’ and I replied, ‘We’ll do our best.’ This request was echoed by many others over the years, and the mention in Miniature is its acknowledgement. The book in your hand is the flesh and blood version of my promise to Tuncay Çavdar. Preparing a detailed, gripping and comprehensive book on ‘bazaar painters’ was going to be a labour of love for Metin And, who is the originator of this term. I believe he had compiled a private file in the ‘sixties or ‘seventies. He does refer to a file on such a book in his writing, but Esra And, who was an expert on her father’s effects, said she never came across it. He might well have been dissatisfied with the quality of his own work and destroyed it one day, or mislaid it during one of the tumultuous periods of his life. The task he set himself was to bring to light bazaar painting, which he regarded as a branch of Ottoman figurative arts, and its producers. It led to articles that received great acclaim between 1985 and 2007 and which include repetitions in terms of subject matter and painting, a few inconsistencies and new discoveries and developments. There might even be contradictions in his readings of some of the paintings. This book will demonstrate that the albums he studied had fascinating stories of their own, their contents intended to illustrate every layer of society in people, architecture and landscape; this study brings to life the act of ‘reading pictures’. Regardless of my comments in the editor’s preface in Miniature, things did move, albeit in their own time. Metin And’s articles on bazaar painters were arranged in chronological order. We are grateful to Esra And for the extraordinary feat of sorting her father’s transparency collection, and making it available to us… In her Introduction: Metin And and the Evolution of Bazaar Painting, Tülün Değirmenci, lecturer at Hacettepe University Department of History of Art studies Metin And’s work on bazaar painting and the value of bazaar painting albums in offering insights into life in the Ottoman Empire, fine arts as well as performance arts, and the history of costumes. Her presence, essay and experience fortified this project and provided its main mast. In addition to shouldering the entirety of the Album section, Tülün Değirmenci also selected the pictures for the Sultans, Courtiers, the Military, Dervishes, City Folk and Heroes sections and wrote brief introductions and explanatory notes.

My humble contribution to the Album is on the subject of hawkers and street vendors, although Metin And had covered this topic in one of his articles. Metin And tirelessly sourced and purchased material to illustrate his articles and books for many years. Faded as they are today, those transparencies are reproduced and cited here. We are grateful to our Teacher and institutions that safeguard them now for allowing their use. I completed the Bibliography, thanks to contributions by my colleague Değirmenci and filling in the blanks left by Metin And. I added a general Index as I have happily done with all his books. He always complimented me on these indexes; I sincerely hope to have done his work justice on this occasion too. Our translator Feyza Howell, who shared the patience of Job as she nudged our caravan back on track with her enthusiastic contributions and helpful hints, and so proved the idiom ‘Learn on the job’ also deserves a mention here. Many thanks are in order… Editor of the English edition, Darmin Hadzibegoviç, contributed to the consistency of the Turkish and English editions with his occasional remarks. He deserves thanks for this. And last, but not least, we must pay tribute to Metin And’s friend Franz Taeschner, who is responsible for this long journey, the owner of the first album he recognised as something quite unique, and who published the first facsimile edition. Bazaar Painters turned out to be a late season joint effort – a demonstration of loyalty. Whether it has succeeded is up to the reader. We remember Metin And with respect in the tenth year of his death. Rest in peace our dear teacher, Metin And…

Acıbadem, 30 September 2018

Introduction:

Evolution of the Bazaar Painting and Metin And Tülün Değirmenci

A Renaissance man according to his friends and colleagues, Metin And was the person who, in addition to his undeniable accomplishments, coined (in his own words) the phrase ‘bazaar painter’ to the benefit of the historiography of art. Not only one of the finest terms in this field, ‘bazaar painter’ is one of the most inspirational. In a series of articles published between 1985 and 2007, And elaborates on this description as he continually updates readers on his latest findings. The articles in this book represent the legacy of a scholar of ‘olden times’ blessed with an exceptionally vibrant scholarly enthusiasm. This introduction intends to summarise Metin And’s research on bazaar painters, specifically his views and findings that developed and occasionally even altered, before attempting to demonstrate the elaboration and changes brought about by new research motivated by his seminal definition.1 A modest postscript to his work collated in this book concludes this introduction with several proposed answers to one of the questions in his articles. This debate will show that the concept And bequeathed to us surpassed a simple definition added to the compendium of history of art terminology, as it additionally assumed the role of a provocative theme that paves the way for young generations in pursuit of fresh new thinking.

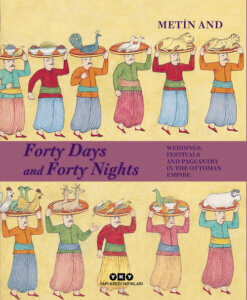

Before moving to these serious matters, however, and emboldened by Metin And’s articles, I would like to touch on the tale of this introduction – it was his gracious acknowledgment of the contributions of his colleagues that has encouraged me to write this personal note. It started with a chance meeting, or more like a stroke of serendipity, at the Yapı Kredi Sermet Çifter Library on 21 October 2008 – ten years ago. I had requested Cinânî’s Kitâb-ı Letâîf (The Book of Wits); the manuscript by this renowned writer and narrator of the time of Murad III (r. 1574-1595) arrived in the hands of Sabri Koz – a vision of the Revered Hızır with his white beard and avuncular smile. He happened to be working on the same tome; intrigued that someone else also wanted it, he had brought this priceless book personally. When I explained that I was working on miniatures, he hurried away with an unforgettable glint in his eyes and returned with a present for me: the commemorative book Yapı Kredi had prepared for Metin And. I recall our excited exchange as we gushed about Metin And and his contribution to Ottoman figurative arts. The same passion defined our voices many years later, when Sabri Koz invited me to prepare this book on Metin And’s articles about bazaar painters. Back to our topic after this brief aside: Metin And introduced this definition that would inspire so much research in an article for the Tarih ve Toplum magazine in 1985.2 What he means in that article and in the preamble to all his subsequent work by his own words is as follows:3 ‘Bazaar painters’ were professional Istanbullu artists who painted to order in their workshops in the bazaar, mostly creating costume albums for their European clients. Foreigners visiting Ottoman lands purchased these albums just as today’s tourists buy souvenirs and post cards. That is the reason why almost all costume albums are found in European museums today. Brief captions in Western languages above or below the figures depicted indicate these albums must have been made for Europeans, although some albums were intended for Ottomans; however, most have failed to survive to our time. This is partly attributable to a national failure to treasure cultural assets (unlike Europeans), and partly to misgivings about figurative representations. The majority of such pieces might have been of an erotic nature, in which case they would have been stashed away and ultimately destroyed. Although there are several albums dating from the sixteenth century, it was in the seventeenth when bazaar painters and their costume albums gained popularity. Their ascendance in the seventeenth century was no accident; the prototype of the genre is the album known as the the Ahmed I Album – although And would revise this view in one of his latest articles. Comprising depictions of daily life without any story line, the work in question pioneered the costume album genre. In terms of the characteristics of the illustrations, bazaar painting was based on the basic scheme developed by court artists; in other words, both groups drew on the same tradition. Yet there were differences too: despite starting out from a common scheme, court artists favoured an additive method, whilst bazaar painters preferred the reductive. In other words, court artists enriched the basic scheme with colour, gold leaf, detail and adornment whilst bazaar painters dispensed with all that they regarded as non-essential, and painted much simpler pictures. This reduced economy of expression approached caricature. Portraits of the sultans are the best examples in this context: a comparison of the two genres highlights the simplicity of bazaar painting. The converse is occasionally true. Selim I (r. 1512-1520) holds a mace in a bazaar painting portrait; another iconographic addition is the sword carried by Osman I (r. 1299-1326).4 I have attempted to summarise Metin And’s general thoughts on bazaar painters above. They frequently introduced his articles and were followed by an account of how he came to be intrigued by the subject. That memory not only signified a section of Metin And’s academic journey, but also contained a charming testimony to recent history. It goes back to the 1950s. Metin And’s interest was first piqued by this genre by Franz Taeschner; the eminent orientalist was a close friend who stayed at the And home during his frequent trips to Ankara. Taeschner’s white beard and kindly face invited a reverential welcome wherever he went with his camera and tape recorder. On one such visit, Taeschner presented Metin And with a copy of his 1925 facsimile edition of an Ottoman album of drawings he had acquired in 1914.5 The original having sadly perished in its safe in the Second World War, And treasured his gift. His fascination prompted a second, equally precious gift from Taeschner: the information that a very similar album was held in Venice. The album Taeschner mentioned was the Cicogna Album (Cod. Cicogna 1971) today held in Venice’s Museo Civico Correr; in his publications Metin And would thereafter refer to it as the V Album. 6 Occupied as he was with Turkish theatre and entertainment, Metin And studied it during a trip to Venice in the hope of finding useful illustrations for his research, and soon began using in his articles the black-and-whites he had commissioned a street photographer to shoot. These photos were also used by his friend and colleague Halil İnalcık, who was writing his The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age (1300-1600). This gesture must have been enormously appreciated by İnalcık at a time predating the digital environment and when access was limited to all manners of information, written or visual. Metin And would repeat this story in numerous articles on bazaar painting; straightaway correctly identifying the albums reproduced by Taeschner and the Cicogna as the work of the same artist, he would posit that the two were complementary, a view that is still held today. In 1965, some fifteen years after that particular meeting, Metin And was invited to give a series of lectures in twelve German cities. He requested that Münster be added to the itinerary with the express purpose of visiting his friend Franz Taeschner. On this, which turned out to be their last meeting, they discussed the Cicogna Album once again, and Metin And complained about his continued failure to access colour photographs of the album. He forgot to ask for the Italian text, something he would later regret as he had no idea whom to consult. Many years later, having finally obtained colour transparencies of the album, and urged on by a close friend, Metin And decided to write on this subject. It was planned to cover seventeenth-century bazaar painters with a specific focus on the Taeschner- and Cicogna Albums. Although he frequently referred to this book as being ready to go to print, Metin And sadly never had the opportunity to do so. The book in your hands that comprises these articles on bazaar painters, therefore, has been compiled as a small consolation or even our duty to Metin And. He narrates this story at the start of every article in his customary warmth and candour, far warmer than today’s distant styles, inviting the reader on his enthusiastic journey. This trait is reminiscent of Ottoman prefaces where the writers pay tribute to a courteous request by a close friend. Metin And never restricts his tales to his own expedition; instead, he relates interesting anecdotes about fellow travellers, and generously expresses gratitude for assistance from colleagues. These tales tucked into the articles not only offer a glimpse into the career of the scholar, but they also bear witness to Turkey’s recent history. His references to Halil İnalcık, the eminent scholar we lost in 2016 is just one such instance. A similar tale concerns meeting İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı as Metin And was busy with the preparations of his Kırk Gün Kırk Gece (Forty days and forty nights). During a train journey from Ankara to Istanbul, Uzunçarşılı was fascinated by And’s plans for this project and gave him a list of the documents in the Ottoman Archives on performance arts and artists. These documents would prove to be priceless for And’s subsequent projects too. Another article opens with his delight at the adoption of his ‘bazaar painters’ term by his colleague Prof Dr Nurhan Atasoy, delight he shares with a great deal of sincerity. In addition to the general essays mentioned above, Metin And wrote on specific themes he had identified in albums he attributed to bazaar painters. Collated in this book, these articles cover, amongst others, hawkers, musicians and Harem women as seen by bazaar painters, thereby offering the opportunity to see collections of pictures on such specific topics. Furthermore, he compares the chroniclers of the time with the depictions whose ‘veracity’ he queries in some of his articles; his most frequently consulted source in this context is Evliyâ Çelebi’s Seyahatnâme (The book of travel). He sets off on the trail of the edifices in these pictures; at times, and especially about buildings in Istanbul, he even consults experts who happen to be friends and colleagues like Semavi Eyice. In other articles, he focuses on specially selected costume albums, such as the Warsaw Album or the Diez Album he believes to have been presented to the Prussian ambassador by Abdülhamid I (r. 1774-1789), for instance. He never forgets to add a regularly updated list of what he believes to be bazaar painter albums mostly held today in European museums and libraries. This book will present the topics I have attempted to summarise here, and much more besides, in the cheerful articles that follow. That is why the rest of this introduction will focus on a variety of studies that, having taken the way Metin And had paved, furthered and occasionally queried his findings.

AFTER METIN AND

One of the most stimulating studies on the costume books attributed to bazaar artists (not, strictly speaking, focusing on bazaar artists per se) after Metin And was the work of Leslie Meral Schick.7 In two separate presentations, Schick makes a series of assessments on the meaning and origins of the costume book in the Ottoman visual tradition rather than the method of production of these albums. She defines costume albums as small handbooks containing portraits of various Ottoman subjects from the sultan through to the court, high-ranking officials and down to the hawkers, the lowest of the common folk. These albums were prepared as guidebooks to Ottoman subjects for curious Europeans just as Metin And had always insisted. In both papers, Schick, who focused on the ‘ranking’ in these albums, deduced the context of the individuals therein to be provided by the costume, given the total absence of any background or spatial reference. In other words, the setting for these figures is their costume. Costume has a close relationship with not only setting, but also status and rank. At any rate, attire is strictly regulated in both Europe and the Ottoman Empire on the basis of social class. Schick associates costume albums that emerged initially within the European culture with regulating and domesticating the ‘other,’ that is, the Ottomans in this context. At the source of this curiosity lies the humanist and proto-anthropological approach of the European tendency to classify everything, which happened to coincide with a similar inclination amongst the Ottomans. In this context, she is intrigued by the similarity between ‘urban’ literature –that classifies Ottoman cities and their inhabitants– and costume books. It is this similarity that has facilitated the adoption and reproduction of costume books. Schick does not comment on the identity of the artists behind these albums in either of her papers, although she does state that Metin And attributes them to bazaar artists before confessing to a degree of scepticism about this theory. Her disinclination to debate the appositeness of such an all-encompassing term suggests that she remains unconvinced by the implication that a single body of artists stood behind these albums. On this point, she is vindicated by Metin And’s intimation in his final article that the group of artists he had originally defined as bazaar painters might indeed have comprised diverse milieux, as the reader will see later. Ground-breaking for researchers as the term ‘bazaar painting’ was, it was not totally without risk – the greatest of which was attributing a large and vastly varied body of work spanning the seventeenth through to nearly the nineteenth centuries, and worse, regarding this group as homogenous. Had Metin And lived long enough to see the most recent pioneering research on the Ottomans, he would undoubtedly have revised his views further, just as he had done in one his final articles. The articles in this book will demonstrate, at any rate, his constant quest to refresh and promptly correct his own work. His assessment of the Ahmed I Album, which will be studied presently, is a case in point. Having repeatedly positioned this volume as the start of the costume album custom in virtually all his essays, in one of his latest articles published in 2005 he pulled no punches as he added the following text which must have caused a few wry smiles: I had, in the past, defined the murakka known as the Ahmed I Album as a prototype for bazaar painters. This is not strictly correct, as other bazaar painting albums predate this particular piece. The real prototype has to be European artists of the sixteenth century as stated above […] As a matter of fact, both views are probably correct to a degree, but are incomplete on their own. The rise of these volumes known as costume albums in Ottoman painting from the seventeenth century onwards must have been greatly promoted by Europeans –both as visiting artists and discerning connoisseurs– as well as the foreign legations that had facilitated the supply to this demand. Yet it is also clear that associating these works exclusively with Europeans fails to grasp the matter. The Ahmed I Album dates from the very start of the seventeenth century, an era when costume albums flourished; the link between costume books and several plates in this exemplar of a new tendency in Ottoman visual tradition is undeniable, as is the role of this album in the fostering of this new tradition. Commissioned personally by the sultan himself in the Ottoman palace, this album proves that interest in the city and its denizens, as well as the events that took place there was not exclusive to Europeans.

THE START OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY: AHMED I ALBUM

Compiled by Kalender Paşa for Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617) at the very start of the seventeenth century and one of the most colourful and fascinating examples of Ottoman painting, the Ahmed I Album [TSMK, B. 408] represents an indisputable milestone for Ottoman painting in both style and content. It is equally indisputable that Metin And was right on so many counts when he identified this album as the start of the bazaar painting tradition. As he remarks, the Ahmed I Album can be regarded as the vanguard of a type of content that subsequent costume books would follow. It not only contains the sine qua non of the genre, the series of portraits of Ottoman sultans, but also, rather like the depictions in costume books, portrays different ‘types’ in the Ottoman world. Another captivating aspect of this album’s focus on Ottoman history, in addition to the royal portraits, is the presence of illustrations of certain incidents in Bayatlı Mahmud’s fifteenth-century chronicle entitled Câm-ı Cem, possibly compiled into a late sixteenth-century manuscript.8 In short, Metin And’s assessment that in content, arrangement and choice of subject matter, the Ahmed I Album was the prototype of a genre that would proliferate in the seventeenth-century might well be considered as correct to a degree. On the other hand, a much more complex palimpsest is indicated by its range of themes; in addition, its manner of production and patronage completely oppose the definition of ‘bazaar painting’. The Ahmed I Album was in effect one of three similar, yet different, volumes prepared by Kalender Paşa for Ahmed I. The first was a murakka of various calligraphic styles [TSMK. H. 2171] and the second was an interpretative book of fortune-telling [TSMK, H. 1703]. Detailed information on the production processes of each of these three manuscripts is offered in their prefaces. The Ahmed I Album preface clearly explains that the manuscript was prepared in response to a direct request from the sultan, who had asked for several precious folios and ‘kıt’a’s to be collated in an album.9 Some of the content is verses in Persian. The pictures in the album fall into a number of categories. The first comprises paintings inspired by Safavid albums and even several direct copies. The second category consists of original Ottoman drawings, single page folios clearly related to the costume books that became popular in the seventeenth century.10 Another group consists of narrative illustrations that are not necessarily accompanied by text. In other words, they relate a specific topic or story through several figures in the composition. Asylum, bath house or mixed parties dominate these paintings mainly on the topic of love; the pictures are placed in order and are believed to be related to love poems in Persian.11 The most unusual group of pictures in the Ahmed I Album comprises individuals usually seen in costume books. Some are generic types representing Ottoman subjects, whilst others must be the heroes of oral and written popular tales, tales possibly narrated in majlises, poetic gatherings. This positioning, affixed as they are on facing pages, as well as the iconographic features of these young males and females appear to support this theory. Young, beardless –and in fact smooth-faced– men are in flamboyant outfits, just like the city boys in Istanbul tales. The daggers at their waists must mark them as ruffians, and the albums in their hands point to their parts in the majlises. In deep décolletés and carrying roses, the young women they face –and occasionally kneel before– are reminiscent of the fictional beloveds who spur their lovers to the most fantastic adventures. Subsequent albums would feature figures very similar to the women in the Ahmed I Album; the traits of their names noted down in titles or captions suggest they were famous in their time. These examples will be covered in some detail later.12 Given all these characteristics, and the evident Persian influence in both design and style, the Ahmed I Album is a direct continuation of the venerable arts tradition that flourished under direct Ottoman court patronage. All the same, the content and stylistic attributes of several of the pictures therein are related to the costume albums that would proliferate throughout the century. Metin And therefore is quite correct in identifying the Ahmed I Album as the vanguard of the bazaar painting tradition. Yet, the study of even a single volume is sufficient to qualify generalisations such as ‘bazaar painters’ to be extremely functional as well as risky, since the research mentioned above reveals that with its style, iconography and patronage, the Ahmed I Album is far too complex and multi-layered to be classified into a broad category. On the other hand, there naturally exist many mass-produced albums, grouped readily by their common traits; Metin And was the first person to remark upon the majority of this group. In an article on seventeenth-century costume albums, Günsel Renda studies a group of volumes produced between 1640 and 1660 and whose stylistic and iconographic characteristics point to the same studio.13 She accredits European travellers and diplomats who had produced books of engravings on their trips to the Ottoman Empire with fostering the costume book genre, and suggests that the seventeenth-century albums which she studied were the Ottoman versions of this tradition. Renda attributes them to artists who ran their own studios in the city; although she adopts Metin And’s definition of ‘bazaar painters’, she does add that there is extremely little information on this group. Her article is a pivotal piece that validates Metin And’s views as it also reveals the vast variety contained in costume albums and the term ‘bazaar painters’. A thorough understanding of the subject is predicated on a classification of these albums, which must be treated as products of an extensive industry. It is equally essential, however, to assess each individual volume in the context of its own production in order to appreciate its finer nuances and to create a more integrated history. As collections of pictures that might well originate from different eras and milieux, these albums present the scholar with more than enough challenges at any rate. The Ottoman material in the Diez Albums in Berlin, named after their compiler, the Prussian Ambassador Heinrich Friedrich von Diez (1751-1817), offers the perfect opportunity to observe this variety as it demonstrates that it is possible to present paintings from different

….

Bu kitabı en uygun fiyata Amazon'dan satın alın

Diğerlerini GösterBurada yer almak ister misiniz?

Satın alma bağlantılarını web sitenize yönlendirin.

- Kategori(ler) Sanat

- Kitap AdıOttoman Figurative Arts 2: Bazaar Painters

- Sayfa Sayısı248

- YazarMetin And

- ISBN9789750864841

- Boyutlar, Kapak22 x 27,5 cm, Karton Kapak

- YayıneviYapı Kredi Yayınları / 2025